Before the Spring 2021 semester Purdue University had no clear and documented way to keep track of all of its UAVs, sensors, and other equipment. A very loose set of guidelines were in place with some almost practically ignored SOP (standard operating procedure). Over the course of Winter break the decision was made to revitalize the UAS major, and with that came an overhaul of how the UAVs and equipment were controlled. The move was made to start getting students more flight time than they ever had received before. Over the course of the entire year of 2020, less than 30 UAVs were dispatched out of the lab area of which they are stored. And while students would graduate with their FAA Part 107 Certification, they would leave with only single digit number of flight hours.

The largest test group for these changes was going to be my AT219 class. The class was being transformed from a basic assembly of a 3D printed UAV, to being a crash course in the higher end UAVs that our program had, which I have documented in part here in my experience blog. Alongside learning and flying these aircraft there was a push to make students more confident pilots by requiring weekly flight hours primarily using DJI Mavic 2 Pros. These Mavic 2 Pros had been covered in our Fall semester AT209 class, but students never had a chance to fly them. And this was just the first step, as all other classes would be making a slightly slower change throughout the Spring semester, but also would have class activities that would require the scheduled use of the UAVs.

The job of how to organize and coordinate the move to have students fly these UAVs in a much greater capacity was given to the instructor of the AT219 class, and PhD student William Weldon. Weldon alongside former student and teaching assistant Kaleb Gould were the primary ones responsible for the creation of the original loose documentation that covered the UAV fleet. Using that original loose documentation Weldon updated it to fit a proper dispatch program that he wanted to develop. A dispatch program would be setup and put in charge of the UAV fleet. The dispatch program would handle all student and faculty requests to checkout an aircraft, prepare aircraft to be picked up, document maintenance related to aircraft, and ensure all equipment was returned. To run this operation Weldon asked three students to run the operation. Senior AET and UAS student John Cox, Senior UAS student and teaching assistant James Hines, and myself Sophomore UAS student Ethan Hoke.

One may question why a Sophomore with little experience like myself would be asked to be a part of the first ever Purdue UAV Dispatch program. While I can’t speak directly as to why Weldon chose me, I can lay out the working relationship we had up unto that point. Over the second half of the Fall 2020 Semester I assisted with some of Weldon’s research for his final PhD paper, and over the Winter break, as documented in my experience blog, I worked on developing 3D printed UAV battery trays for storing our batteries. So, while I may not have been the most knowledgeable student about the fleet, his willingness to give me this amazing opportunity came from my willingness to assist on things outside of the classroom. But from the beginning I knew I would have to push myself to prove a mistake was not made by giving me this opportunity.

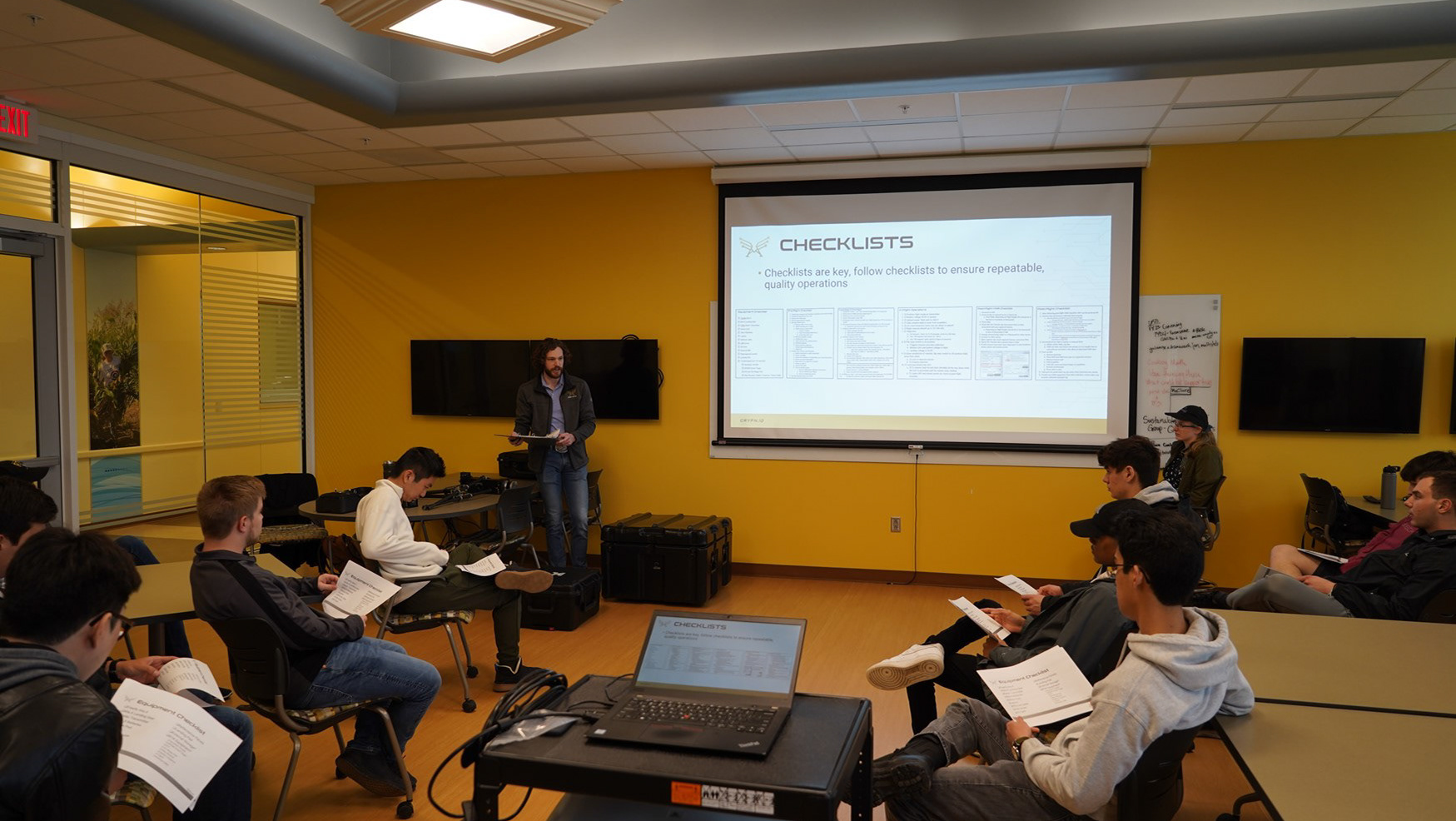

At the start of the semester the dispatch team got its bearings over how thing would need to function day to day. Firstly, dispatch request were to be receive using a filled-out document submitted via email. So, all dispatch officers created sets of email rules to separate out these requests from other emails. Secondly, was how to keep track of these requests. The simplest solution we had was to print them out and clip them to a magnetic whiteboard in the office. On the day of the request the UAV would be prepared utilizing the requested equipment on the request forms and going through a Vehicle Preparation Checklist that had been developed the previous semester. This process involved inspecting the aircraft, ensuring all components of the aircraft were present in case, charging batteries and controllers, ensuring sensor functionality, and checking the UAVs for software updates. When students would arrive to pick up their requested aircraft a dispatch officer would provide them a Metadata sheet, and a Return Form both to be filled out before returning the aircraft. The Metadata sheet included space for the student to write down the actual location of the flights, the METAR used to check weather conditions, duration of the flight, characteristics of the sensors used, and more. The Return Form helped ensure a student brought back all the equipment they initially checked out.

With the base infrastructure in place we began working starting the second week of the semester. Despite the cold weather students began attempting to get their flight time in. This however would come to a quick stop after a harsh realization. That harsh realization being that all of the aircraft were not currently properly registered with the UAV, with most having expired registration. This caused us to have to shut down for a week to get everything properly reregistered. This however also gave the dispatch team time to go through and better document everything the program had and get more UAVs. At the beginning of the semester the program had 6 Mavic 2 Pros for the AT219 class to share. This was by far to drastically low of a number for roughly 26 students to share each week. So, 10 more were ordered, alongside several more batteries. During this downtime dispatch worked hard to document the serial numbers of all UAV related equipment, setup all the newly acquired DJI Mavic 2 Pros, ensure every UAV was properly registered with the FAA, and clean up and better organize the lab in which all of the equipment was stored. Dispatch was only down for just over a week and resumed full operations thereafter.

As February moved into March, and temperatures started to rise more classes in the UAS program looked to start dispatching out aircraft. This presented the next major challenge for the dispatch team. Using a combination of an email and paper system made keeping track of the increased number of dispatch request became minorly difficult. While the number of aircraft no longer was a bottleneck, the number of batteries did. While more batteries were ordered, there were not enough to send out 4 batteries out with each Mavic 2 Pro for example. This limited the number of either aircraft that could be sent out with students or the number of batteries that would go with each aircraft. To add to the complexity with handling of charging batteries. While we had an abundant of chargers, students would keep aircraft overnight at times. This meant that aircraft would sometimes come back with drained batteries that we would have to do our best to get them charged before they needed to go back out to other students. Luckily most students were understanding of the situation and while at some dispatch request had to have their pickup times pushed back, we were able to successfully able to navigate around the limitation until more batteries were received in mid-April.

As April turned to May and finals were upon the students of Purdue university. There were still plenty of students finishing up flights at this time, but the small downturn in the number allowed us to start preparing to tally up everything for the semester. Here is what the first ever Purdue University UAS Dispatch teams were able to pull off.

*Handling of 588 received dispatch requests

*According to flight data tracking platform Measure Ground control 3483 flights were flown, and 646 hours of flying occurred

How do these numbers compare to before the dispatch program was started? Well Measure Ground Control showed that in the whole year of 2020 only roughly 25 hours were spent flying. This is roughly backed up by any existing documentation from the time frame. Let’s assume that another 10 hours weren’t tracked do to the non-enforcement of Measure’s software utilization. This would still mean that students spent 18 times more hours flying, And on top of that, there were ZERO aircraft sustained major damage. Only minor damages were sustained over the course of the entire semester with the primary one being small amounts of prop damage. While propeller damage is not ideal it is common with UAS, especially with training flights, and was still a rare occurrence, happening on average once every 158 flights With this many hours spent in the air, it is truly an amazing accomplishment.

And with this accomplishment of helping get students more flight hours, I am happy to say that I was a part of the first ever Purdue UAS Dispatch Team. It wasn’t a perfect experience by any stretch. There were a lot of growing pains, lessons learned, and stressful moments. But working alongside John Cox and James Hines meant that even at the hardest times nothing was impossible. And a special thanks to William Weldon, for being there every step of the way, and helping prove to the other faculty that this program is worth having. I look forward to working to continue to improve this dispatch program to the best of my abilities to better serve the other students. But as James Hines and William Weldon move forward with their lives and away from Purdue University things will certainly be different.