In the first week of this semester I was approached by one of my professors in a design and technology class. I had filled out an “about me” survey before the beginning of the semester for this class, and he knew I had experience in UAS. For this class we have a semester long project, and he wanted to let me know that in one of the labs there was a UAV that was left behind by an instructor that moved to a different university. As this class isn’t in the aviation or forestry department, I didn’t expect to have the opportunity to work with a UAV in this class, so I asked to check out the UAV to see what kind it was, and what state it is in.

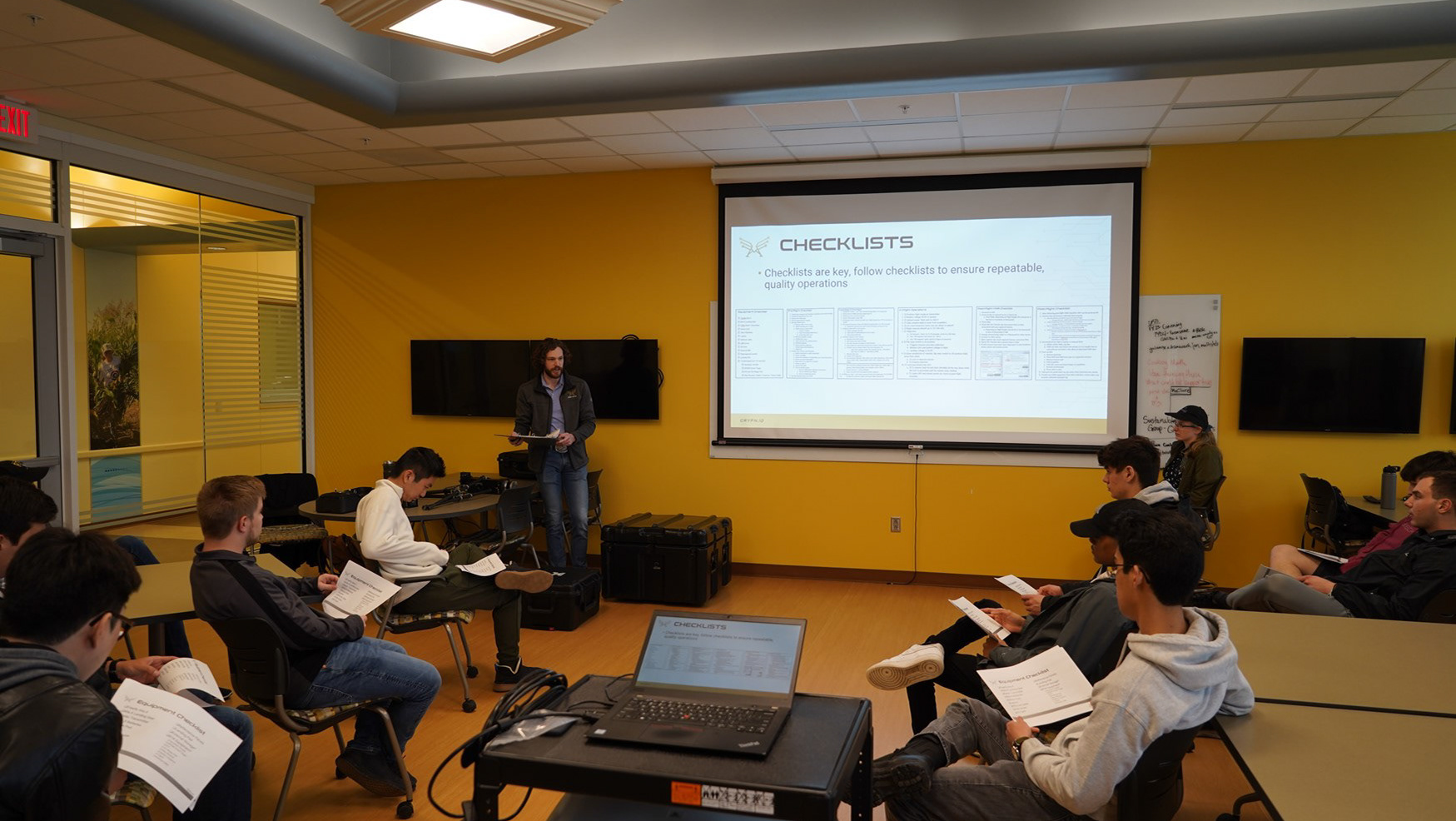

Keeping proper records and documentation for any UAV is important, as these vehicles may change hands/stewardship from time-to-time after people leave an organization or retire. As such, records of the last time it was flown, who flew it, who it is registered to, records on accidents and repairs, cycles put on batteries, and any other important notes are crucial to ensuring someone unfamiliar with the past of the UAV can understand the current condition of the UAV and operate it safely. This is important for hobbyists, commercial operators, and students to all understand and follow a consistent practice of. Luckily, I have had experience in this kind of record keeping and UAS assessments, thanks to my internship at GRYFN and prior work for the UAS departments dispatch program.

The UAV ended up being a DJI Phantom 4 V2. The professor told me that he had no idea the last time it was flown at all, so I began a cursory glance through the hard case it resided in, to ensure all necessary equipment was in there. In the hard case was the UAV, 4 batteries, controller, wall charger, car charger, 8 props, a variety of paperwork, several ND filters, lens caps for gimbaled camera, and two USB-A to Lightning cable. A fun surprise came in the form of an attached 3rd party sensor. The sensor is from a company called Sentera and was a NDVI (or Near Infrared) sensor. Having accounted for everything in the case I took the UAV back to my apartment to take a closer look at it.

Since I had no idea when the last time the UAV was flown, my first task was to ensure the batteries would still charge properly. All four of the batteries and the controller indicated a battery life of two and a half bars. This would indicate between 50%-75% battery life, however from my previous experience with DJI products I knew this was supposed to be the auto discharge state of the batteries after sitting for a long time. Upon plugging the batteries in the battery life bars dropped to a flashing one bar, which indicates very low battery life remaining.

While the batteries and controller were charging, I began taking a further look through the rest of the case. I started with the UAV, which appeared to be in very good condition. I didn’t find any cracks, scratches, or other signs of wear. Something missing from the UAV, however, was a registration label. From there I moved to paperwork in the case, which included all the manuals for the aircraft, batteries, and controller. In the stack of papers was also a small pamphlet for the sensor which talks about the company Sentera’s software Field Capture and Field Agent. Field Capture appeared to be a desktop application for data processing, and Field Agent appeared to be a mobile app for flight planning and execution. The paperwork bundle also included a thank you note from the hard case manufacturer, and a Part 107 reminder notecard I would assume was included by either Sentera or the hard case company. Missing from the paperwork stack was any information about UAV registration, which had me believing that the UAV may have never been registered by its original owner or operator.

Continuing through the case I examined the props. Five of the props were unwrapped and looked to have been used, while three remained in plastic wrap. The five unwrapped props all had small scratches and what appeared to be little marks left behind by dirt. Since the UAV was free from any such marks this confused me, as if the previous operator had crashed the UAV, there would be marks on the airframe too. The props did not have any cracks or chips though, so I deemed them still safe for operation. Finally, I evaluated the controller while it was still on the charger, and found it to be in good condition, though there was some slight discoloration on the back.

While batteries continued to charge, I removed the micro-SD cards from the UAV and from the NDVI sensor. Neither of the SD cards had data from a previous mission on them, which shows potentially good data practices from the previous operator. On the SD card from the NDVI sensor though I found a file structure designed for the sensor. This included a “User Profile” document which included some values that could be changed depending on how you wanted to capture data using the sensor. I read through these options but left them all the same for the time being and returned the SD cards to their respective slots.

The next day once the batteries and controller were fully charged, I began further testing. Since the Phantom 4 is an older product, it works with DJI’s older Go4 app. This app was not available in the Google Play Store for my Samsung Galaxy S20+, but I was able to download an APK and install the app that way without any trouble. I powered on the controller, connected my phone, and then powered on the UAV. Everything turned on, and the controller connected quickly to the UAV. I was immediately prompted in the Go4 app to update the “DJI Fly Safe Database” which is DJI’s own database of restricted area’s and LAANC area’s for UAS operations. After that update, I was prompted to update the firmware of the UAV. Both updates were successful the first time with no issues.

Once into the Go4 app I was immediately presented with a live feed from the camera, and a warning message that the UAV needed a compass calibration done. While not ideal to conduct compass calibrations indoors, I went ahead and did so just for the time being. This calibration cleared the error message, and all other systems reported no errors. While looking for error messages from other systems I also took note that the UAV had good satellite GPS connectivity in my apartment. I then placed the UAV on a table and walked around it to test its obstacle avoidance sensors, which all responded to my movements, but slower than some of DJI’s newer products. I triggered the camera from the controller and my phone, and the UAV responded appropriately each time. The gimbal moved freely without any stuttering as well.

The Sentera NDVI sensor was also powered on with the UAV, and had a few LEDs illuminated on its side. The stabilizing gimbal for it appeared to be functional as well, as it didn’t move out of place when I tried pushing it. Without any real documentation for the sensor itself I conducted some small attempts of data collection with the UAV inside my apartment. Nothing I did in my apartment changed the indicator lights on the NDVI sensor at all. I landed and removed the SD card from it to check if it had collected anything. There was no captured data on the SD card, so I went to the “User Profile” document again and changed it so the sensor would capture data every 2.5 seconds. My understanding was that this would be while the UAV was in flight, so I tested a small flight in my apartment, but once again the NDVI sensor captured no data.

I decided to try a different app to see if it would make a difference, so I loaded up Litchi on my phone and conducted another short flight with it. This sadly did not lead to the capture of any data though. However, this did ensure that the UAV was still safe to fly and had normal flight characteristics for a DJI product, both with the DJI app and a third-party app.

Since I was struggling to collect data on the NDVI sensor, I turned to the internet to see if I could find any documentation for the sensor, or support page. I did find one website you could purchase the sensor from that included all its hardware specifications, but no operational documentation. The Sentera website also did not include any sort of documentation, accept mentions about what was possible their Field Agent app. The app was not available on the Google Play Store for my phone, so I had a friend in the UAS industry download the app on his iPhone and report back to me what he saw. While the app was free to download for him, he was immediately presented with a login screen, with no option to create a new account. If you clicked on the “Terms and Agreement” link it mentioned in the first paragraph about having a valid license and the terms of that license applying to use of the app. I went back to Sentera’s website and found that the “Basic” license cost $500 per year.

Under the assumption that this app with a license is required to collect data using the sensor, my quest for data collection stopped here. While this was disappointing to me as I was curious about the images the NDVI sensor would collect, I was happy that at least I could take the UAV back to the professor and tell him that all the standard aspects of the UAV were fully functional. This series of testing the UAV though wouldn’t have been necessary if more in-depth documentation was kept with the UAV.

As stated in a previous blog post I was a member of the first iteration of the UAS dispatch team for Purdue University’s UAS program. A major part of that job was documenting as much information as possible about each UAV as feasible. Understanding the registration status of UAV is an important legal factor. Knowing if the UAV suffered damage from a crash or other accident is an important safety factor. Having readily available notes or documentation for 3rd party add-ons is important for people unfamiliar with the UAV operating it. And battery cycle records can help operators understand potential impacts of battery degradation that may impact flight planning. I am happy though that I was able to lend my expertise to evaluate the current state of this UAV and provide notes about its current operational state so that if myself or other students choose to use it in the future, there will be a documented point of evaluation to start from.